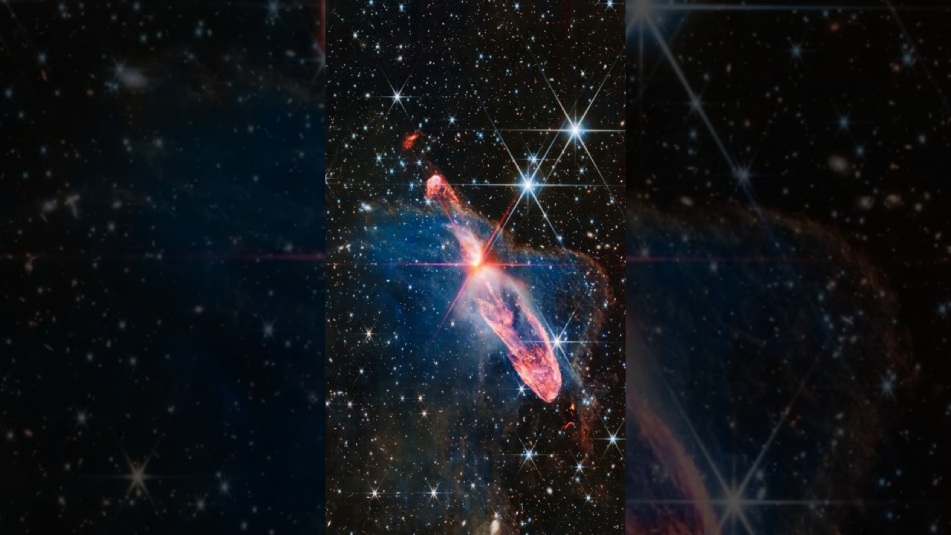

The uncommon and brief explosion from a couple of child stars has been deified in another picture from the James Webb Space Telescope.

The double star and its eruption is called Herbig-Haro 46/47, and it has a place with a class of probably the most dynamite objects in the Smooth Manner. Known as Herbig-Haro objects, they’re positively gorgeous, but at the same time they’re deductively significant since they can assist us with understanding the arrangement cycle of child stars.

The development of a Herbig-Haro object requires a specific arrangement of fixings. It begins with a child star still during the time spent framing, known as a protostar.

Protostars structure from denser bunches in a generally thick haze of gas and residue that breakdown under their own gravity and begin turning. As they turn, they spool in increasingly more mass from the cloud around them.

A portion of this material, cosmologists accept, doesn’t make it onto the star. Rather, it is whisked away along attractive field lines around the beyond the protostar, and advanced towards the shafts. At the point when it arrives at the posts, it is sent off away at high velocities as a collimated stream. It’s basically the same as the interaction by which dynamic dark openings send off jets.

The protostar planes can then punch into the encompassing cloud material and the extraordinarily high temperatures included transform that material into plasma. This produces two shining curves on one or the other side of the protostar, which is as yet covered by a thick torus of residue and gas.

So you get these shining patches of nebulosity emitting from a dull, dusty mass.

JWST’s infrared responsiveness implies it can look into the residue, since infrared light doesn’t dissipate the manner in which different frequencies do. So the telescope can allow us to look inside those dusty bunches to investigate the child stars in that.

HH 46/47 is two or three thousand years of age; stars require a long period of time to frame, so the double star is just barely getting everything rolling. JWST’s new picture shows two orange curves from a previous explosion, revolved around a sparkling orange-white mass. That is where the stars are, in their thick birth cloud.

A later explosion is seen at the 2 o’clock diffraction spike, as strings of a more sensitive blue. What’s more, the light blue ribbon like material around the whole construction is a dim cloud, which ordinarily seems to be a mass of shadow overhead. Here, it is delivered straightforward to JWST’s infrared eye, so we can see the more far off stars and universes past.

The planes of a child star are believed to be vital to the development of a star. They steadily will assist with shooting away the cloud around it, preventing the star from becoming any greater – however permitting the completely developed object to sparkle openly across the ranges of room.