One of the fundamental building blocks of life, amino acids, are probably not going to be lacking in any lifeforms that reside in Venus’s poisonous clouds. That’s what researchers claim is the outcome of a recent lab experiment, at least.

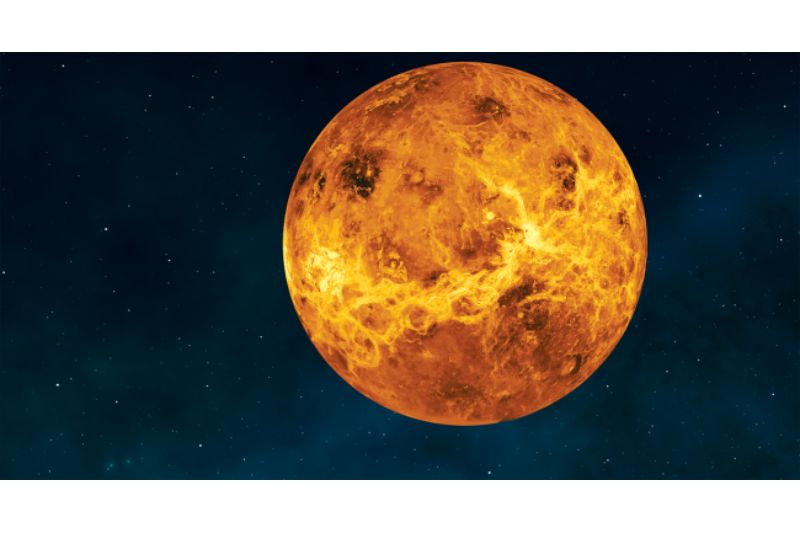

Though Venus is Earth’s “twin,” it sizzles at hundreds of degrees and is shrouded in clouds of sulphuric acid, a colorless, toxic liquid that erodes teeth, dissolves metals, and irritates noses, throats, and eyes. Because of this, it isn’t thought that the rocky planet is much of a home for living things; it’s certainly not as friendly as planets like Mars, Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, or Saturn’s Enceladus appear to be. Scientists believe that any life that may have developed in Venus’ harsh atmosphere could be found drifting in its toxic clouds, which are cooler than the planet’s surface and may therefore be home to some unusual forms of life.

“It doesn’t mean that life there will be the same as here. In fact, we know it can’t be,” scientist Sara Seager of MIT, a co-author of the new study, stated in a statement, “In fact, we know it can’t be.” “But this work advances the notion that Venus’ clouds could support complex chemicals needed for life.”

In order to simulate the conditions found in Venus’ clouds, Seager and her colleagues dissolved 20 “biogenic” amino acids early last year. These molecules are necessary for all lifeforms on Earth because they aid in the breakdown of food, the production of energy, the development of muscle, and other processes. The vials contained sulfuric acid and water. Her team spent four weeks dissecting the structures of these amino acids, which included arginine, histidine, and glycine, among others. They discovered that, in spite of the extremely acidic environment, the molecular “backbone” of 19 of the molecules remained intact.

“People have this perception that concentrated sulfuric acid is an extremely aggressive solvent that will chop everything to pieces,” said Janusz Petkowski, co-author of the study and member of the Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) department at MIT. “But we are finding this is not necessarily true.”

Leading the investigation was undergraduate student Maxwell Seager of Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts. “Just showing that this backbone is stable in sulfuric acid doesn’t mean there is life on Venus,” Seager said. “But if we had shown that this backbone was compromised, then there would be no chance of life as we know it.”

Nine of the twenty amino acids that the team examined are also present in meteorites, which suggests that Venus may have also received those chemicals from meteor strikes, according to the researchers.

A highly anticipated, privately-funded expedition to Venus scheduled for January of next year will be focused on looking for molecules similar to these in the planet’s dense clouds. This project, known as the Venus Life Finder, will send the spacecraft Photon flying by Venus and insert a tiny, single-instrument probe into the planet’s atmosphere. In order to evaluate Venus’ potential for habitability, the parachute-less probe is intended to identify organic chemicals as it descends through the atmosphere and transmit data back to Earth before being destroyed.

Principal investigator Sara Seager remarked, “I think we are just more happy than anything that this latest result adds one more ‘yes’ for the possibility of life on Venus.”