Indigenous peoples residing on the Great Plains of Montana and southern Alberta may trace their beginnings to ice period antecedents according to the Blackfoot Confederacy’s old ancestry, which dates back 18,000 years, according to a recent DNA study.

A group of scientists lead by two Blackfoot Confederacy members looked into the genetic heritage of their tribes for the latest study, which was published on April 3 in the journal Science Advances.

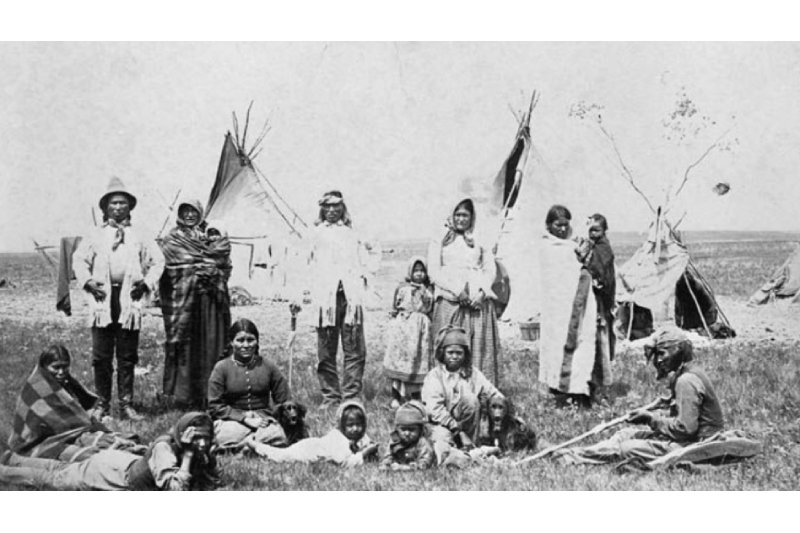

The Blackfoot Confederacy was originally made up of four related tribes: the Blackfeet, Kainai, Piikani, and Siksika. Its people were nomadic bison hunters and trout fisherman. The U.S.-Canada border split their land in the middle of the 19th century, and the governments of both nations forced the Indigenous confederacy members to relocate to reserves in the late 19th century.

Even though archeological findings and oral histories attest to their extensive history in the region, tribes belonging to the Blackfoot Confederacy have since had to justify their claims to land and water. In order to further scientific understanding of Indigenous genomic lineages and to support their treaty rights, members of the Blackfeet tribe in Montana and the Kainai Nation in Canada collaborated with scientists from several U.S. universities to explore their genetic history.

The seven bones that the study team carbon-dated to between 1805 and 1917 provided samples for whole-genome sequencing during a time when Blackfoot-Euroamerican connections were growing due to the fur trade. Although the samples originated from skeletons that had been exposed on a burial platform, which made DNA preservation less than ideal, every one of the remains yielded mitochondrial DNA information, or genetic information inherited from the mother. Six members of the tribe today also had their entire genomes sequenced.

A significant portion of the genomes of the modern Blackfeet/Kainai and their historical forebears were found to be shared by the genetic data, indicating a biological link. Although this genetic continuity was predicted, the researchers also discovered that this lineage differed from previously documented Indigenous populations in North and South America. The team’s hypothesis, based on statistical modeling, is that many population waves from a single source spread out across the enormous geographic expanse of the Americas during the Late Pleistocene, some 18,000 years ago, when the Blackfoot people split off from other tribes.

The study’s framing is crucial, too, says Graciela Cabana, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville who was not engaged in the research, in addition to uncovering this hitherto unidentified chromosomal variety. Cabana emailed Live Science, saying, “It’s pretty obvious that this was written from more of an Indigenous voice.” “It’s actually rare to see a collaborative study that is actually led by Indigenous community members on Ancestors.”

Genetic anthropologist Ripan Malhi, co-author of the study and a University of Illinois graduate student, emailed Live Science to suggest that genomics research be carried out by members of the community who can apply this tool from an Indigenous perspective, “or through a community-collaborative approach where community partners have equal control in how the research is conducted and reported.”

According to co-author Maria Zedeño, a research anthropologist at the University of Arizona and co-director of the Blackfoot Early Origins Program, this study is a result of documenting Blackfoot persistence in their ancestral land, she told Live Science in an email. “Genomics study is only one project in this program,” Zedeño added, and “the tribal leaders reviewed its design and development at every step of the process.”