Homo humans left behind little clues about their whereabouts when they migrated out of Africa and returned 20,000 years later to Eurasia. And in the interim, where had they gone? According to a study, Homo sapiens left Africa during that enigmatic time and settled on the Persian plateau.

According to fossil evidence, early Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa at least 210,000 years ago. However, genetic evidence indicates that the most successful migration wave occurred around 70,000 years ago, and all non-African people living today are descended from this large wave.

However, there are very few fossils of Homo sapiens in Eurasia from 60,000 to 45,000 years ago, which is why the researchers of the new study decided to find out where modern humans migrated at that time.

The study, which was published on March 25 in the journal Nature Communications, revealed that the Persian plateau was the most ideal place for human occupancy during this time using climatic models and genetic data.

Some disagree with their conclusions, arguing that additional data is required.

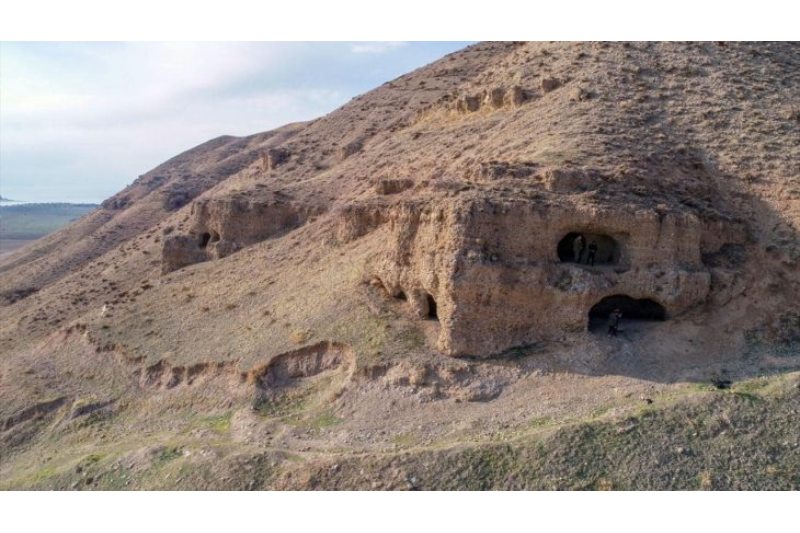

The majority of modern-day Iran, the Persian Gulf, and Mesopotamia are all part of the Persian plateau, which the researchers identified as a population hub in a prior study. The study proposes that between 70,000 and 45,000 years ago, all modern non-Africans may have had ancestors who resided there.

In a recent study, the scientists examined data from paleolithic Eurasian genomes and compared them with archeological findings indicating advancements in stone tool technology. They concluded from this that modern people most likely gathered in a population center that functioned as the starting point for several migrations across Eurasia. However, the current study incorporates a paleoclimate model, which was necessary to deduce the population hub’s homeland.

The researchers concluded that the Persian plateau was the region most likely able to support a population hub by modeling the distribution of a hunter-gatherer Homo sapiens population and reconstructing areas that had favorable environmental conditions for human occupation between 70,000 and 45,000 years ago.

Additionally, there are established Neanderthal fossil sites on the Persian plateau whose dates coincide with the emergence of Homo sapiens. Lead author of the study Leonardo Vallini, a molecular anthropologist at the University of Padua, emailed Live Science, “Admixture [coupling] with Neanderthals occurred during this timeframe, so it is possible that it took place inside the Hub.” “It is also possible, however, that the two groups were avoiding each other and the interactions were much more sporadic.”

According to Vallini, Homo sapiens were hunter-gatherers at this crucial stage of human evolution and growth. However, it’s likely that important information was exchanged here. In their study, the researchers speculated that the center “might have served as an incubator for the development of cultural innovations” such projectile weaponry and rock art.

Still, other experts think that additional data is required to identify a potential population center. In an email to Live Science, biological anthropologist Sang-Hee Lee of the University of California Riverside, who was not involved in the study, said that the new research raises visions of a bustling hub of ancestral human occupancy. Lee questions whether the palaeoecology theory is appropriate for early humans, though.

“Paleoecology data from the ‘Hub’ rely on a single data point in Iran,” Lee stated, alluding to the only data point that the study authors provide to support their theory that the hub was a friendly location. “Of course, an absence of evidence does not mean an evidence of absence,” Lee said.

The authors of the paper agree that additional information on climate and hominid fossils is required to support their theory.

However, the authors of the study said that if the Persian plateau was a population center for tens of thousands of years, then this crucial area is perfect for looking for fossils and paleoecology information that could help explain the missing pieces of the puzzle about the migration patterns of early humans across Eurasia.