Massive explosions on the Sun’s surface this year could provide major clues about whether life has ever lived on Mars.

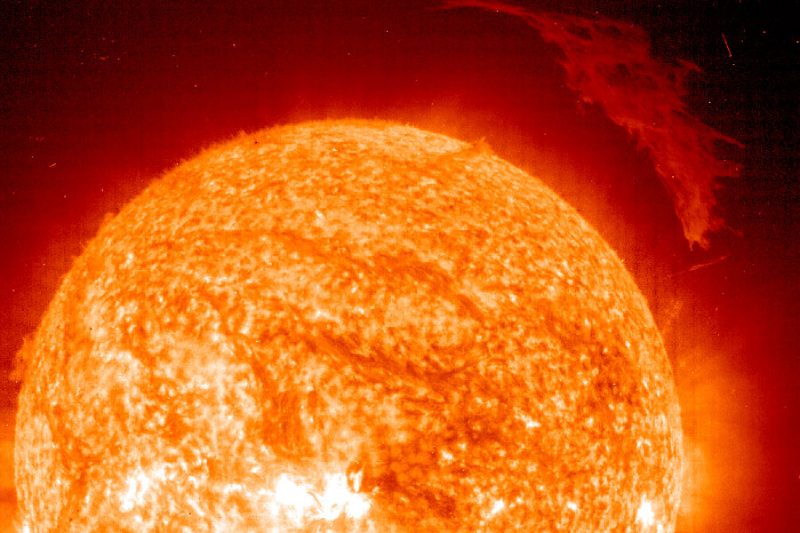

The massive, blazing volcano at the center of our solar system reaches what NASA refers to as its “peak activity” around every 11 years.

In essence, it gets more violent, erupting into space on a far more frequent basis with scorching hot eruptions.

For the Sun, 2024 is one of those historic years that could determine whether NASA moves forward with its goal of sending humans to Mars for the first time.

However, it goes far beyond that, and in the process, it should give scientists the foundation they need to learn more about the possibility of extraterrestrial life on Mars.

NASA plans to concentrate its research efforts on examining these massive explosions occurring on the surface of Earth’s star starting at the end of 2024. Alternatively, the Sun may be “throwing fiery tantrums,” as NASA says.

Given that Mars lacks a magnetic field, understanding solar activities will be essential for sending astronauts to the planet.

While Mars lacks this luxury and must deal with the consequences of solar outbursts quite aggressively on its surface, Earth is protected from most of them by its magnetic field.

The goal is to investigate the precise effects of solar explosions on astronauts and potential shielding methods, should the decision be made to deploy them in the first place.

The Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) and Radiation Assessment Detector (RAD) spacecraft of NASA will be positioned above the Martian surface to investigate the effects of these solar storms on surface phenomena.

In the ongoing quest to verify the existence of extinct life on Mars, the RAD spacecraft will be crucial in determining when and why such life may have ended.

“You can have a million particles with low energy or 10 particles with extremely high energy,” stated Don Hassler, the Southwest Research Institute’s chief investigator in Boulder, Colorado, who oversees RAD.

The only instrument that can see the high-energy particles that get through the atmosphere and reach the surface, where humans would be, is RAD, even though MAVEN’s instruments are more sensitive to lower-energy particles.

Scientists will continue to benefit from data from RAD in their understanding of how radiation degrades carbon-based compounds on the surface.

In order to determine whether any evidence of prehistoric microbial life is still present there, this procedure may be essential.

Shannon Curry of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado Boulder is the principal investigator for NASA’s MAVEN orbiter.

“For humans and assets on the Martian surface, we don’t have a solid handle on what the effect is from radiation during solar activity.

she stated.

“I’d actually love to see the ‘big one’ at Mars this year – a large event that we can study to understand solar radiation better before astronauts go to Mars.”