Known by another name, brown adipose tissue (BAT), is a form of fat found in our bodies that is distinct from the more common white fat found around our thighs and abdomen. Brown fat performs a unique function in that it aids in the conversion of calories from meals into heat, which is beneficial, particularly when we’re exposed to low temperatures, such as during cryotherapy or winter swimming.

Brown fat was long believed to be exclusive to small animals, such as mice and infants. However, recent studies indicate that some adults retain their brown fat throughout their lives. Because brown fat burns calories so well, researchers are attempting to figure out how to safely activate it with medications that increase its capacity to produce heat.

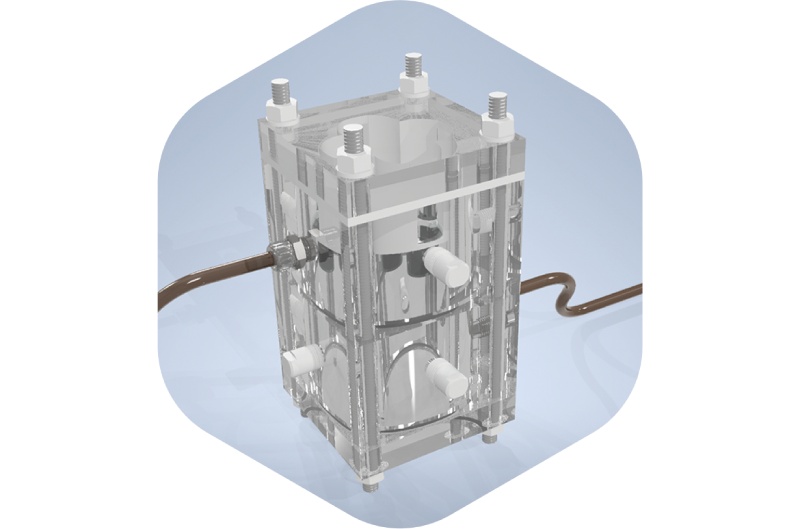

Brown fat has a previously unidentified built-in mechanism that turns it off soon after it is activated, according to a recent study from the research groups of Prof. Jan-Wilhelm Kornfeld from the University of Southern Denmark/the Novo Nordisk Center for Adipocyte Signaling (Adiposign) and Dagmar Wachten from the University Hospital Bonn and the University of Bonn (Germany).

This restricts its efficacy as an obesity therapy. The team has now identified a protein that is in charge of this switching-off mechanism, according to the study’s first author, Hande Topel, a senior postdoc at the Novo Nordisk Center for Adipocyte Signaling (Adiposign) and the University of Southern Denmark. The name of it is ‘AC3-AT’.

Tapping the “off switch” enables a fresh tactic

Using cutting-edge technologies to anticipate unknown proteins, the study team discovered the switch-off protein. Hande Topel clarifies: “When we investigated mice that genetically didn’t have AC3-AT, we found that they were protected from becoming obese, partly because their bodies were simply better at burning off calories and were able to increase their metabolic rates through activating brown fat” .

After receiving a high-fat diet for 15 weeks, two groups of mice developed obesity. In addition to gaining less weight than the control group, the group who had their AC3-AT protein eliminated had a healthier metabolism. “The mice that have no AC3-AT protein, also accumulated less fat in their body and increased their lean mass when compared to the control mice” adds co-author Ronja Kardinal, a PhD student at the University of Bonn in Dagmar Wachten’s lab at UKB. “The mice that have no AC3-AT protein also accumulated less fat in their body and increased their lean mass when compared to the control mice.”

Hope for weight-loss-promoting tactics

While brown fat is less common in older people and adults have less of it than in babies, it can still be activated by certain factors, such as exposure to cold. When it is triggered, it speeds up these people’s metabolism, which could also aid in stabilizing weight reduction when calorie intake is (too) high.

According to co-corresponding author Prof. Dagmar Wachten, co-director of the Institute of Innate Immunity at the UKB, member of the ImmunoSensation2 Cluster of Excellence, and of the Transdisciplinary Research Areas (TRA) “Modelling” and “Life & Health” at the University of Bonn, “However, further research is needed to elucidate the therapeutic impact of these alternative gene products and their regulatory mechanisms during BAT activation”.

According to co-corresponding author Prof. Jan-Wilhelm Kornfeld of the University of Southern Denmark, “Understanding these kinds of molecular mechanisms not only sheds light on the regulation of brown fat but also holds promise for unraveling similar mechanisms in other cellular pathways. This knowledge can be instrumental in advancing our understanding of various diseases and in the development of novel treatments”,